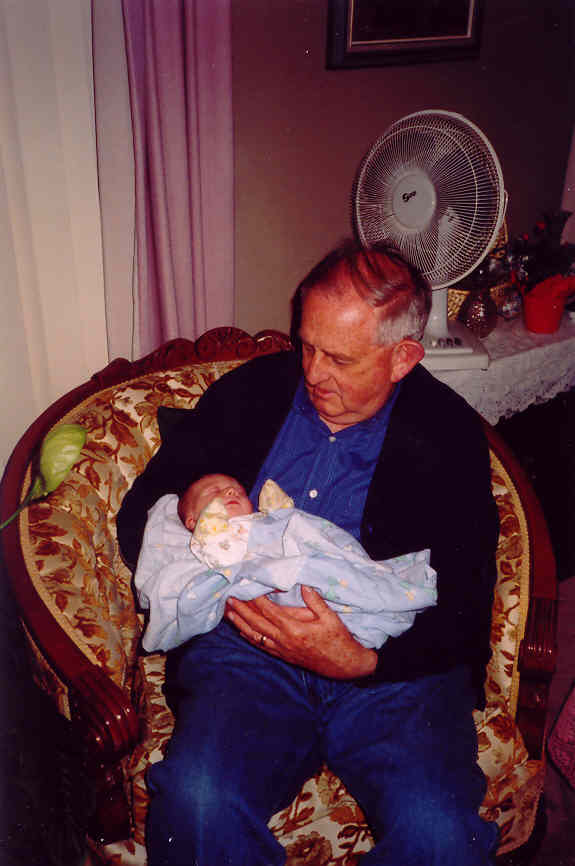

Yesterday, December 6th, was the 8th anniversary of my father’s death, and as always on these anniversaries, I had a glass of wine in his honour. Now, me drinking wine in the evening after the kids are in bed is nothing unusual, but when I’m toasting Dad, I go to a bit of extra effort. Instead of opening any old plonk that happens to be handy, I take the time to find a bottle of nice wine, the kind of wine Dad would enjoy.

In life, Dad had a true appreciation for fine wine, and he had an impressive collection. Where I’m the kind of person who will buy a bottle of wine and promptly drink it, Dad actually collected it. Every bottle he got was meticulously marked with the date of acquisition, and if it was a gift, it would also be marked with the occasion and the name of the person who had given it to him. The wine would then be put into one of the wine cabinets and left to age as appropriate.

Dad belonged to the Wine Of The Month club, and the bottles he received from them were treated to the same attention to detail. His last shipment arrived about three weeks before he died, and as sick and fragile as he was, he waved away offers of help and lovingly made his annotations on each bottle.

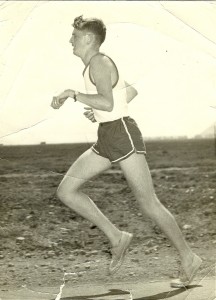

A love of wine is just one of the things I shared with Dad. We spent many evenings sitting out on his patio, enjoying the last of the day’s warm South African sun, sipping wine as we discussed the other interests we had in common, like running or books. Even after I moved to Canada, we chatted to each other about what wine we were drinking. It always felt as though I was still drinking wine with him, even though he was on the other side of the world.

And so, the first time I opened a bottle of wine after he died, it felt a little odd. It didn’t feel right, somehow. Dad clearly didn’t think it was right either, because judging from how that particular wine-opening went, he was there and he was trying everything in his power to prevent that wine from being opened.

The scene unfolded two days after Dad’s funeral. My mom, my brother and I were having lunch at my aunt Ann’s house, along with some of my cousins. Lunch at Ann’s house was always a feast. She was – may she rest in peace along with Dad – a master in the kitchen. Her fine food had to be accompanied by fine wine.

While the others sat chatting at the dining room table, I was in the kitchen with Ann. She was transferring food into serving dishes, and I was opening the wine. In those days, most bottles of wine had corks. Not that weird composite plastic stuff you get these days, but real, honest-to-God corks.

I did my thing with the corkscrew, and the cork came partway out of the bottle, and then it just stopped. You know how corks sometimes just get stuck, and no amount maneuvering will get them to budge? This was one of those corks. I was not deterred, though. I had several years as a university student behind me – I was capable of getting any wine out of any bottle, no matter what impediments stood in my way.

I extracted the corkscrew from the cork, grabbed a breadknife, and used it to saw off the bit of cork that was sticking out of the top of the bottle.

I could almost hear Dad spinning in his coffin.

I set about using the corkscrew on the remaining piece of cork. I got it firmly in place and then started the process of getting the cork out.

The corkscrew broke.

So to sum up the situation I had the following: a wine bottle with half a cork in it. Said half-cork had half a corkscrew in it. And most importantly, there was wine inside the bottle that was stubbornly remaining inaccessible to us.

By this stage, Ann and I were in absolute stitches of laughter. Ever the graceful hostess, Ann did a skilful job of politely heading off anyone who tried to come into the kitchen wanting to know what was so funny.

Fortunately, Ann was a great believer in contingency planning, so she had a backup corkscrew which she produced with a flourish, like a magician. Through a series of hit-and-miss stabby attempts, we finally got the cork out.

The good news was that we had freed the wine within the bottle. The bad news was that it was riddled with cork.

No problem.

Ann and I strained the wine into a plastic measuring jug, rinsed the bottle to get rid of any stray bits of cork, and then restored the wine to its rightful receptacle. I mean, we had to. There was no way we could show up to the dinner table bearing a plastic jug full of wine.

That hard-earned wine was some of the best I ever tasted, as if the person whose life we were toasting had sprinkled a little bit of magic into it.