When my son was first diagnosed with autism nine years ago, I went to my local bookstore in search of help. I was looking for books that would tell me how to deal with the sensory eating issues, the grocery store meltdowns, the head banging incidents that left dozens of holes in our drywall. I wanted to know how to get my son to talk, to make friends, to play with toys instead of spending hours staring at a piece of string.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that I didn’t need an instructional manual. I needed to know that I was not alone, that there were people out there who knew what I was going through as the parent of a child with autism, and above all, that my family and I would survive. We would figure out all of those things that I was so desperately looking for, and we would, in time, adjust to our new version of reality.

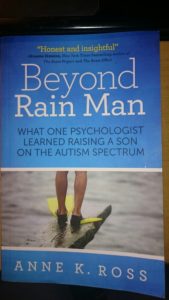

While I was enduring this phase of post-diagnostic angst, psychologist Anne K. Ross was going through experiences that she would later capture in the pages of a wonderful book. Beyond Rain Man tells the story of a woman who, having devoted her life to helping children with developmental disabilities, was thrown for a loop when her son was diagnosed with Aspergers Syndrome.

With compelling bravery, the author tells the story of her son’s childhood. She describes his struggles, the tears and the triumphs, and the ups and downs of the relationships within her family. As an autism parent, I can relate to so many of the stories Anne tells in her book: the impact of her son’s Aspergers on his younger brother, the challenges of keeping a marriage healthy when there’s so much going on, and the endless concerns about the future.

I do not feel as if I read a book. I feel as if I sat on a couch chatting with the author over a cup of coffee, learning about her experiences and how she and her family got through them.

If time travel was a thing, I would toss a copy of Beyond Rain Man to that earlier version of myself who was desperately searching bookstores for answers. I would make the book magically appear in front of her, and I would tell her that this is the book she needs to make her feel less alone and more hopeful.

Kirsten Doyle was given a copy of “Beyond Rain Man: What One Psychologist Learned Raising A Son On The Autism Spectrum” by Anne K. Ross, in exchange for an honest review.