Today I took George to the doctor to get his shots. I was very nervous about this prospect: George used to have a terrible fear of doctors, and would always sit in the waiting room literally quivering with anxiety until it was his turn. Fortunately he’s a healthy child and hasn’t needed the services of a doctor for a couple of years, so I curious to see what his reaction would be like today.

When we walked into the waiting room, he sat down and calmly started playing with a toy. He didn’t flinch at the sights and smells typical of a doctor’s waiting room. We didn’t wait for long before we were called into the doctor’s inner sanctum. There, too, George was remarkably laid back as the doctor looked him over.

His composure fell apart somewhat when it was time for the needles, but as soon as they were done and the Band-Aids applied, all he needed was a couple of minutes of hugging, and then he was fine.

Ah, yes. The needles.

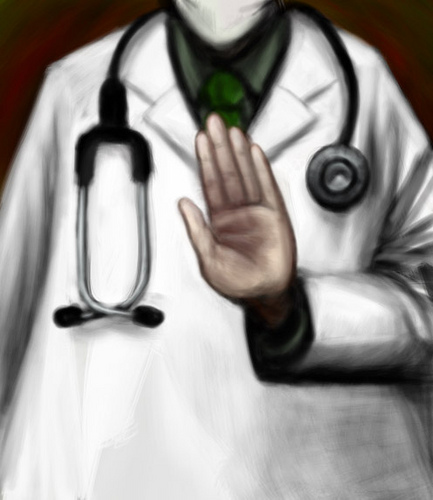

As an autism parent who keeps her kids vaccines up to date, I sometimes feel like a minority voice. Or perhaps it’s just that the anti-vaccine people tend to be more vocal than those on my side of the fence. But this is not intended to be a post about who’s right and who’s wrong. Everyone has their own journey, and their own reasons for the choices they make.

My position – speaking only for myself – is that vaccines cannot be blamed for the autism epidemic. You can show me a thousand statistics proving that I’m wrong, and I can show you a thousand statistics proving that I’m right. I do not dispute that some people have bad experiences with vaccines. But I do not believe that anyone has made a convincing enough case to generalize those incidents to the population as a whole.

I know with absolute certainty that George came out of the womb with autism. When I look back over his babyhood, I remember many thoughts of doubt going through my mind.

He should be swatting at toys by now, but he stares right through them.

Shouldn’t he be interested in the texture of these fabric books?

At what age are babies supposed to sit? Crawl? Walk?

Why is he ignoring me when I call his name?

I knew early on that something was going on. Vaccines had nothing to do with it.

Still, there are people who are critical of my choice to vaccinate. Deciding to vaccinate my younger son was like walking through a minefield.

“You are vaccinating your younger child, even though your older child has autism? Really?”

From the way some folks talked, you would have thought I was ripping out my child’s fingernails one by one.

My kids’ vaccinations have always gone without incident. There are generally a few tears that are forgotten by the time we are getting back into the car, and there may be an evening of crankiness. Someone might sleep badly. By the following day, everyone is pretty much back to the way they were.

My name is Kirsten, and I willingly vaccinate my child with autism.

(Photo credit:Daniel Paquet.This picture has a creative commons attribution license.)