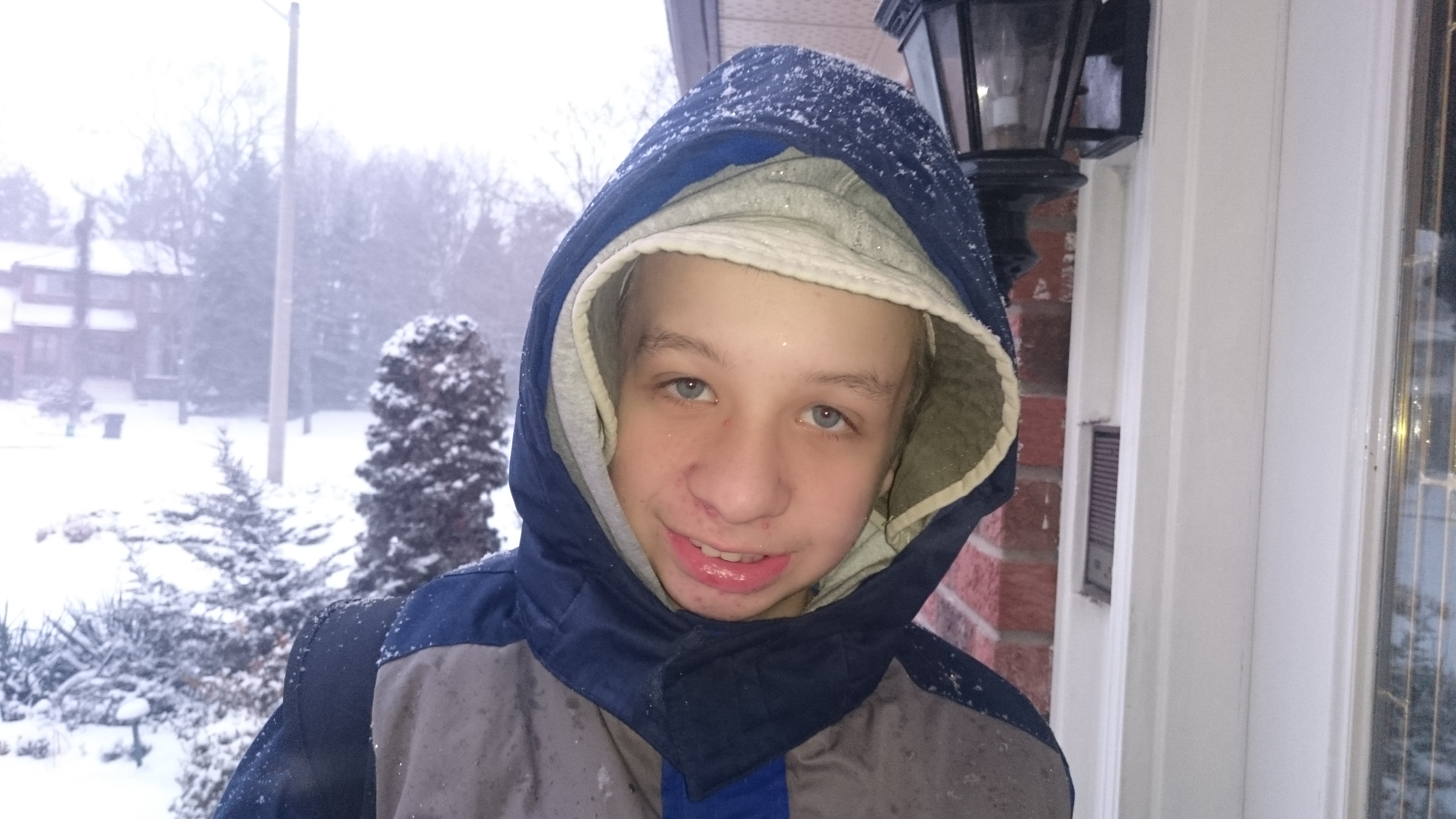

Today we continue our series of stories about children with autism in Ontario. The Ontario government’s recent announcement that IBI services are no longer available to children aged five and older has had devastating consequences for many families, including the family of six-year-old Xander. If you have a story to tell, send an email to kirsten(at)runningforautism(dot)com.

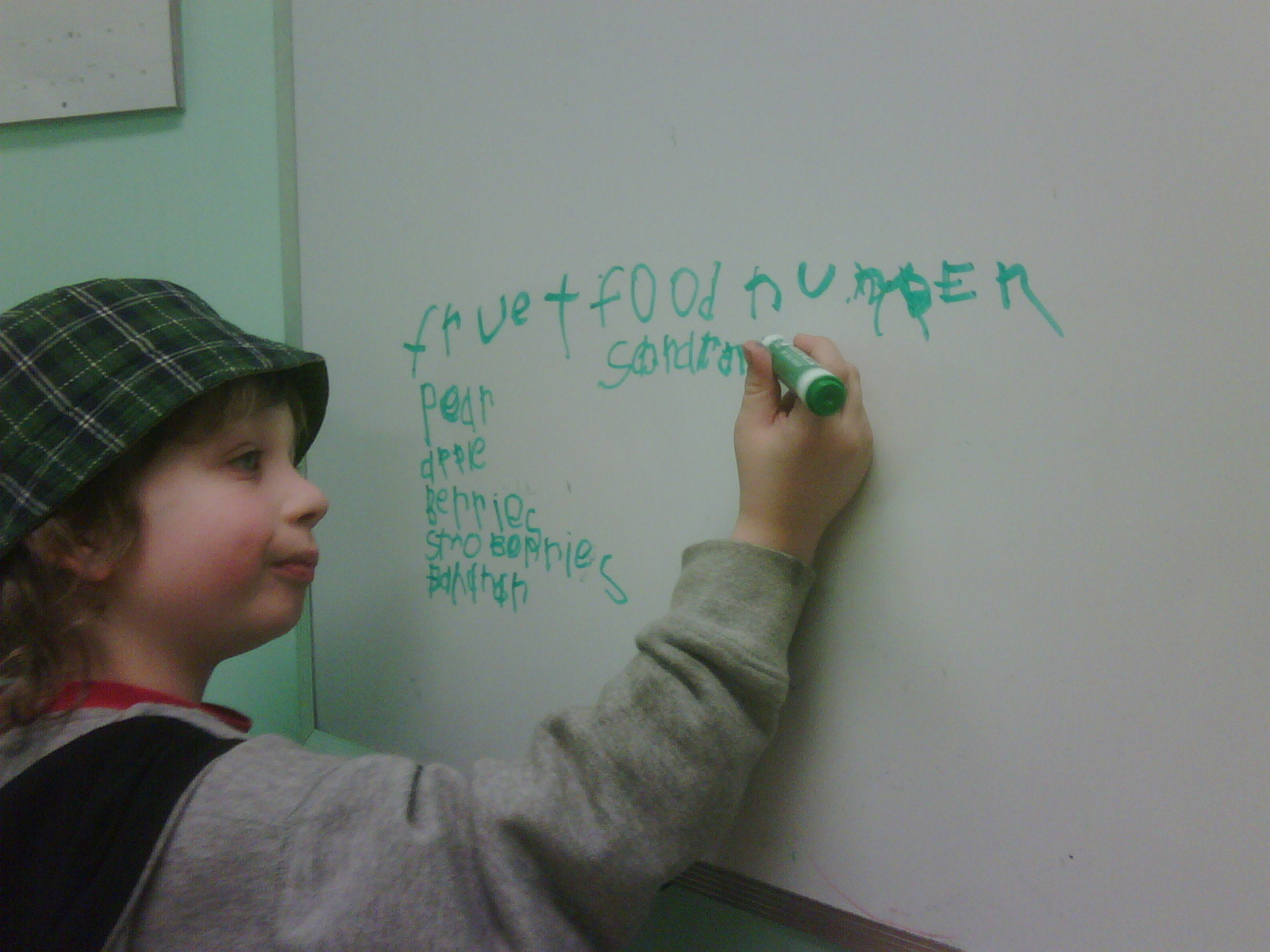

When Xander started provincially funded IBI services in December 2015, his family breathed a sigh of relief. He was two months shy of his sixth birthday, and he had been on the waitlist for three years. His initial baseline assessment showed delays in several areas: he was not consistently responding to his name, his vocabulary was extremely limited, and he struggled with tasks like tracing letters and using scissors. Back then, he could not even tolerate sitting at a desk for any length of time.

Xander’s IBI team identified fourteen therapy goals for him to work towards. That is a lot for any child to accomplish. But Xander quickly became a poster child for the effectiveness of IBI therapy.

Within three months, he had accomplished – and in some cases surpassed – every one of those fourteen therapy goals. He was responding to his name and he could recite his home phone number. His vocabulary was growing steadily and he was learning to make requests verbally. He developed the ability to follow simple instructions, and he could now sit at a desk working for up to ten minutes.

In other words, IBI had given Xander the building blocks, a solid foundation upon which to build. In the next phase of IBI, he was going to build on that foundation and learn how to use his newfound skills in a functional, meaningful way.

That, at least, was the plan. Then the Ontario government came along with its announcement that IBI will no longer be provided to children aged five and older. Children of that age who are already receiving IBI services are going to be phased out of the program.

This news has been a devastating blow to Xander’s parents. In just a few short months, they saw their son start to blossom. Now they are faced with the prospect of him losing access to a method of intervention that has unlocked all kinds of potential in him. The future, that was looking so full of promise, is once again uncertain.

The Ontario government is trying to sugar-coat this by saying it is in the best interest of the kids. They are offering affected families one-time payments that do not come close to making a dent in the expense of IBI therapy. The alternative services they are offering to older children is not nearly as effective as IBI.

Xander’s story is one of a myriad tragedies affecting Ontario families in the wake of this announcement. He is living proof that IBI can and does work for older children, and unless some kind of miracle happens, he could become living proof of what happens when you remove such a crucial service from a child with autism.

By Kirsten Doyle. Photo courtesy of Xander’s mom, Shannon.