My son George hops off the yellow school bus and bounds up the driveway with his fingers in his ears – a throwback to last summer, when the sound of the tree-feller’s chainsaw hurt his ears. He shucks off his backpack, removes the hoodie that he will not abandon even during the height of the summer, and kicks off his shoes. Then, and only then, am I permitted to talk to him.

“How was school?” I ask him, as I always do.

“School was fine,” he says, as he always does.

“What did you do today?”

He doesn’t reply. Instead he starts peering at the brim of his hat, or running a finger along the edge of the door frame.

“George?” I ask, needing to engage him before he gets too far into his own head. “What did you do at school today?”

“School was fine,” he mutters.

“Tell me one thing you did today.”

“Played outside,” he says, after a pause.

“And what did you do outside?” I ask, hoping I’m accomplishing the tone of gentle persistence that I’m going for. He cannot feel forced, but he needs to know that I’m not giving up on this conversation. It’s a delicate balance some days.

“Kicked the soccer ball,” he says.

“Wow, that sounds like fun!” I say effusively.

Sensing that he’s fulfilled his obligation to talk, he runs off to turn on his computer. I sit on the stairs for a moment, feeling both exhausted and elated by the fact that I actually had a conversation – albeit a brief one – with my son. For most kids, this kind of exchange would not be a big deal. For George, it is.

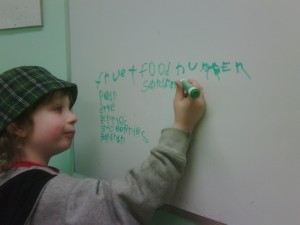

George, now eleven years old, was diagnosed with autism when he was three. We had him assessed because he wasn’t talking, and even though he has come a long way since then, his speech and communication skills are far below those of his typically developing peers. This comes with a number of challenges, but there is one challenge in particular that I have never really spoken about.

How do I know if he’s OK?

I’m not talking about “OK” in the physical sense. George is able to tell me when he feels sick, or when a part of his body is hurting. He has even started to identify emotions, telling me when he’s sad or angry.

What I’m talking about is whether he’s “OK” from a mental health perspective. With my younger son, who is typically developing, it’s fairly simple. I have conversations with him, I talk to him about how he’s feeling, and from his natural expressiveness I can get a sense of whether everything is all right or not. I am well aware that childhood depression is a very real problem, I know what signs to look out for, and I have a reasonable degree of certainty that I would recognize it in my younger son.

With George, it’s a little more complicated, and from a statistical standpoint, it’s more of a concern. Individuals with developmental disabilities are more likely than the general population to experience mental illness, but they are less likely to be diagnosed, because it’s less likely that the people around them will realize that something is wrong. George, with his speech delays, does not have the words or the cognitive functioning to describe depression in a way that would enable me to recognize it.

Even the behavioural cues present in typically developing children may be different for those with special needs. It is easy – far too easy – to blame everything on autism. When a child with autism has a meltdown, or starts to cry for no reason, or gets lost inside his or her own head, everyone assumes it’s because of the autism. That is not unreasonable: in many cases, it is because of the autism.

But what about those times when it isn’t? What about the times when a child is banging his head against the wall because his mind is in a dark, desolate place and he doesn’t know how to express it? What if the other-worldliness is not symptomatic of autism, but of withdrawal? What if no-one realizes that depression has become the child’s companion, because in their well-meaning attempts to manage the autism, they just haven’t thought to consider anything else?

These concerns are part of what drives me to try to have conversations with George. Every single thing he can tell me – no matter how small it might seem – is like a golden nugget that I treasure. I lavishly praise his attempts to communicate, and every day, I encourage him to tell me something – anything – that happened to him that day. It is my hope that if, at some point, anything is going on in his life or in his mind that he needs help with, that will be the thing he tells me about that day.

This is an original post by Kirsten Doyle, written for APA’s Mental Health Blog Day. Picture attributed to the American Psychological Association.