There are many people who think you have a cushy job, with seven-hour workdays and two months off every summer. They say that you are overpaid, underworked, lazy and uncaring. Any time there is a labour dispute in the Ontario education system, like there is now, you are accused of trying to suck the taxpayer dry in order to line your own pockets.

Let me tell you what I think, teachers.

I think you guys totally ROCK.

Since my firstborn son started school in 2007, I have gained an appreciation for just how hard you work. I have come to understand that your workdays extend far beyond classroom hours, that report cards and IEP’s involve a lot more than simply punching data into a computer, and that a great deal of thought and time goes into the lessons you teach and the projects you assign.

Being a teacher is HARD. You have to juggle the needs of your students, the demands of their parents and the rules of the Ontario education system. While you understand that other people sometimes have bad days, you are on your game all the time. You spend your days doing a job that most people wouldn’t want for all the money in the world – which is kind of ironic, considering that many think you should be paid less.

While people across Ontario have been hating on you for pursuing your right to do your jobs properly, you have kept going, helping my boys learn and grow, giving your work the same dedication and focus that you always have. Here are just a few of the things you have been doing, over and above teaching my kids.

* You have taken my son and rest of the track and field team to their competition events. Even now that the competitions are over, you are still showing up at school early so that those kids who want to continue their morning runs can do so.

* You have taken your eighth grade classes on their graduation trips, and you have been hard at work planning extra-special graduation days for them.

* You came to school early one morning on a day that you were not assigned to teach, just so that you could fulfil your before-school yard duty and ensure the safety of my son and his friends.

* You hefted a cardboard box out of your car one Monday morning, and when I asked what it was, you said that it was projects you had graded over the weekend, as well as materials for an upcoming student assignment that you had prepared and photocopied on your own time.

* You dug around in your classroom searching for a book that you knew my son would enjoy reading during the summer.

* You organized a water play day for the younger kids, and you allowed my son and his classmates to help run it, so that they could develop their leadership skills.

* You have not gone to bed before midnight for the last week, because you’ve been putting together picture slideshows and videos for your Kindergarten class’s graduation celebration.

* You have been tirelessly working on ways to help my autism boy develop his speech and communication skills, and you have been helping him develop life skills that will take him far beyond the classroom.

Here’s a little something that I know about you, teachers. You don’t just do this for the money. You do it because you truly care about the kids you are teaching. This is more than “just a job” for you. When you go to work every day, you are not simply earning a paycheque. You are shaping futures and opening up worlds of opportunity for my boys.

I will miss getting report cards for my boys this year. I will miss reading your carefully thought out commentaries on what their last term of the school year has been like. It will be strange to not see their grades for each subject.

But I understand why you’re not doing them. I understand that you are taking on a government that wants to choke the Ontario education system and make it more difficult for you to teach my kids effectively. There are people who are trying to claim that this is all about money and benefits, but I know that is so far from the truth that it might as well be on another planet.

I know that right now, you are not fighting for yourselves. You are fighting for my children. You are fighting for the future of our society.

For that, I thank you. Stay with the fight, teachers. And when you hear or read about parents criticizing you for taking a stand, know that there are parents out there who completely support you.

Sincerely,

A grateful parent

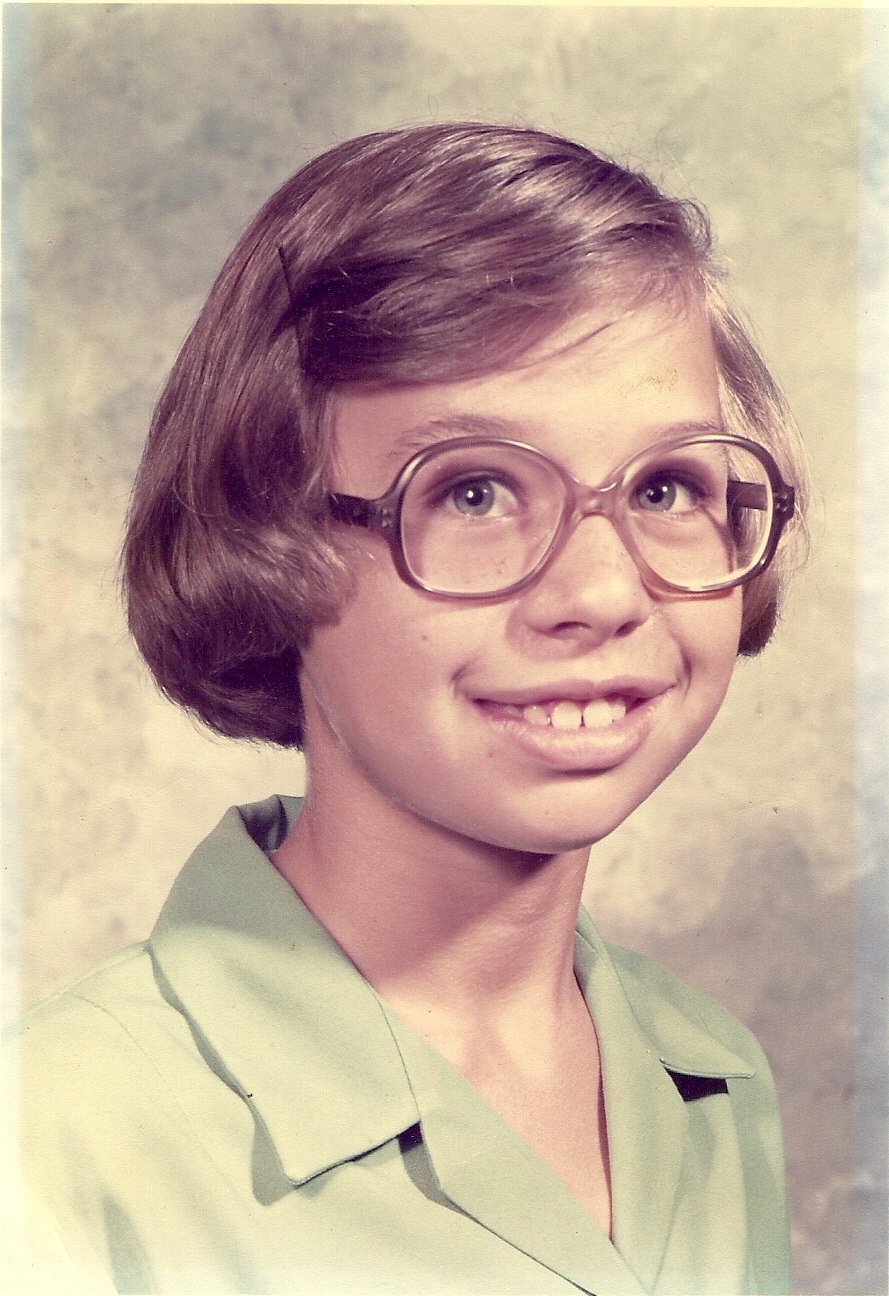

This is an original post by Kirsten Doyle. Photo credit: woodleywonderworks. This picture has a creative commons attribution license.