Today’s post is going to look a bit like a speech from the Oscars, only there’s no red carpet, I’m not wearing a ballgown accessorized with diamond jewellery, and I didn’t get a funny little trophy thing. Instead, there is the finish line of a race, a sweaty old running outfit accessorized with a space blanket, and a finisher’s medal. Just setting the scene so you can picture me as I start my speech.

<clears throat and waits for the audience hubbub to die down>

My 2014 autism run is now almost a week in the past. I have one day left of sitting on the couch doing nothing post-race recovery. The stiffness in my legs is gone, my knees have recovered, and the chafing from my sports bra is fading. Even the Ankle of Doom is feeling pretty good. I am almost ready to lace up my shoes for an easy run, and I have started thinking about my race calendar for next year.

I want to thank my mother, because people always start by thanking their mothers. And because my mom is awesome. She lives on the other side of the world, but I felt that she was part of the finish crowd cheering me on last Sunday. Thanks also to my brother, who is a loyal supporter and a great friend.

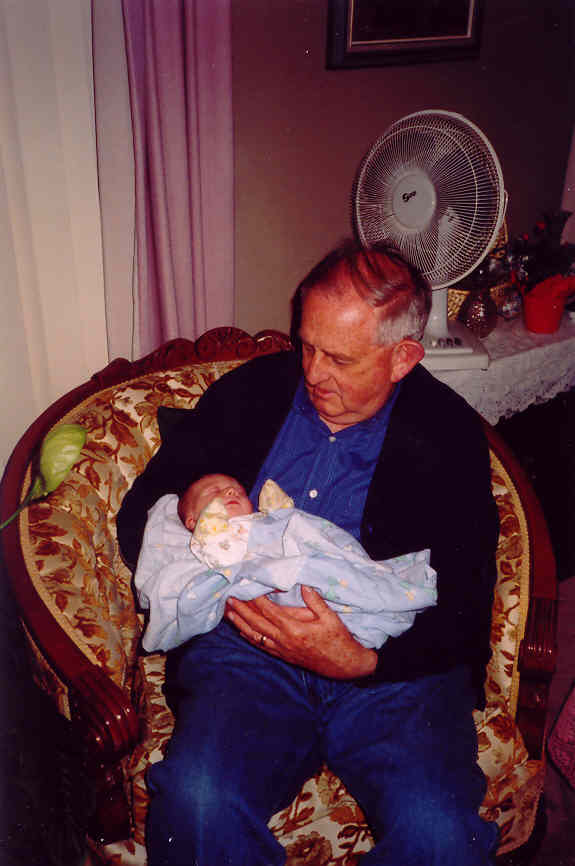

I want to thank my Dad, who was an elite runner in his youth and the first to fuel my love of running many years ago, in a previous life. Dad was a superb runner, and he always believed in me. He is no longer with us, but I still feel his presence when I run, and he was definitely with me on race day.

I want to thank the organizers of the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Half-Marathon and 5K for putting on a fantastic event. Everything was great, from race kit pickup right through to the post-race food. I enjoyed almost every minute of the race, and I even made it through my troublesome 18K patch better than I ever have before. I had enough energy in reserve at the end to really belt it out in the last kilometre, and the look on my face in my race picture tells you how I was feeling as I sprinted to the finish line.

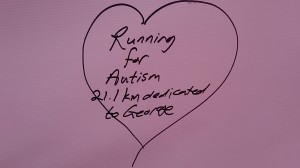

Thank you to the Geneva Centre for Autism, not only for being a constant source of support for my family since George was diagnosed with autism in 2007, but also for getting me off the couch and into my running shoes a little more than five years ago. It is a true honour to be affiliated with this organization that has given countless autism families the most precious of commodities: hope.

Thank you to all of the people who sponsored me. Your generous donations are going to make a real difference for so many kids. Thanks to you, children and youth with autism will be able to learn how to play musical instruments, participate in sports teams, attend social skills training, go to summer camps, communicate via iPads and much more. Opportunities are being created for my son and other kids like him, thanks to you. My appreciation for your support has no bounds.

Thank you to the runners in my life, who have always been there with words of advice and encouragement when I’ve needed it. You have celebrated with me after the good training runs this season, and you have commiserated with me when the going has been tough. You know what it’s like – the long runs on rainy days resulting in squelchy shoes, the uncomfortable chafey bits where you didn’t apply enough Body Glide, the runs that are just bad for no reason – and you always encourage me to keep going.

Thank you to all of my non-running friends, who tolerate my running-related social media postings: the race-time status updates, the moans and groans about sore muscles, the Instagram pictures of my training watch. You are kind enough to like and comment on my posts, you tag me in running-related things that you think I will like (and I do – I love all of them). Your messages of support and love last Sunday were overwhelming, and they meant the world to me.

Thank you to my husband, who holds the unenviable position of being the partner of a runner. Over the course of the season, he made sure I could get out for my long runs and races, and he tended to my aching muscles with the right combination of concern and humour. The night before the race, he sacrificed sleep so that I could rest undisturbed by children, and he got up early to make sure I got to the start line on time.

Thank you to my younger son James, my tireless supporter and cheerleader. He cheerfully saw me off for my long training runs throughout the season, and he always welcomed me back with a hug, even though I was stinky and sweaty. He is a fantastic champion for his brother’s cause: it was his idea for me to run in a cape last Sunday, to “get into the spirit for autism”. His energy is contagious, and I took a bit of it with me on my race.

The final thank you is reserved for George, my older son, my brave and amazing autism boy. George is my inspiration. He is the reason I get up early in the morning to run in the dark, the reason I do ten-mile training runs in the midsummer heat, the reason I am willing to get rain in my running shoes on wet days. George teaches me about life every single day. And when I am struggling through a run, feeling like it will never end, thoughts of George get me through. I tell myself that this kid lives with autism every hour of every day. That doesn’t stop him from being one of the most determined people I have ever encountered. If he’s not going to give up, then neither am I.

This is an original post by Kirsten Doyle. Finish line photo credited to Marathon-Photos. Picture of runner’s wall message credited to Kirsten Doyle.