As a person who (a) suffers from social anxiety disorders and (b) is a bit of technogeek, I have very few friends who I have actually met in person, and quite a lot who I have communicated with only through the magic of the Internet. It is always a bit of a thrill when I can actually meet – face to face – one of my online friends.

Yesterday I got that opportunity, when a friend who lives a couple of hours away came to visit with her husband and little boy. We all had a wonderful time. My friend is even more fun in person than she is online, and we already have plans in the works to meet up again.

When this absolutely delightful family left, my husband went off to his factory to admire his latest handiwork, and I settled down in the living room to watch Olympic swimming and weave words into pictures.

The kids wandered onto the deck to play, and I was easily able to keep track of them from where I was sitting. All I had to do was turn my head from time to time to make sure I could still see them, and as long as I heard the thump-thump noise of their feet hitting the wooden deck as they ran around, I knew the status quo was being comfortably maintained.

At one point when I looked around, James seemed to be somewhat taller than usual. Also, he was holding a long stick. I was so comfortable in my seat, though, and since no-one was screaming I decided that it would not be necessary to actually get out of my seat. A verbal reprimand issued at reasonable volume should suffice.

“James, put the stick down!” I called.

“But then George will try to get the Lego off the roof,” he called back.

What???

I went out to the deck, and there was James standing on the table, poking at the roof with the stick. I stepped back a few paces and almost tied my neck in a knot in my efforts to bend it far enough, and sure enough, I just managed to make out the unmistakable bright yellow glint of Lego.

“How did it get there?” I asked, perplexed.

“I threw it there,” said James in a matter-of-fact tone, as if this kind of thing happened every day.

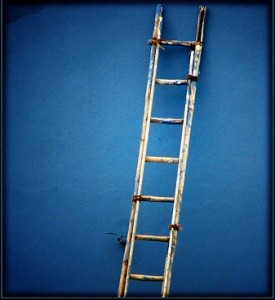

There are times when parenting should operate on a need-to-know basis, and I decided that this was something that I did not need to know. I went into the back yard and lugged the ladder onto the deck. I set it up, and stood there looking at it with growing anxiety.

Here’s the thing. I am absolutely petrified of ladders. I always imagine that something terrible will happen while I’m up on one. The thing will collapse beneath me and I will crack open my skull and break seventeen bones. Or it will fall over and I will be trapped on the roof forever, subsisting on bugs and droplets of water from the rain gutter.

If I didn’t get the Lego, however, George would have a meltdown of epic proportions. The fact that I got up on that ladder and made my shaky way to the top is proof that I love my children more than life itself and would do absolutely anything for them.

At the top of the ladder, I had a bit of a problem. Because of where I had positioned it, I couldn’t see where the Lego was. I had only one shot at this, though. Once I got down from the ladder, there was no way in hell I was getting back up again. So I closed my eyes, gritted my teeth, and ran my hand along the bit of roof that was within my reach.

My hand made contact with something hard. Hoping to God that it was the Lego, I grabbed it and tossed it down onto the deck. I then made my nervous way down the ladder, only allowing myself to breathe once my feet hit terra firma.

The thing that I had thrown down from the roof was indeed the offending Lego. I breathed a sigh of relief, half-heartedly reprimanded the culprit (James) and in a rare break from the norm, allowed myself a glass of wine before dinner.

My poor shattered nerves deserved it.

(Photo credit: aloshbennett. This picture has a creative commons attribution license.)