A few months ago, George went through a phase of tying one end of a rope to his ankle, and the other end to the ankle of a willing or not-so-willing participant. He would then insist that the other person walk with him to wherever he wanted to go. He didn’t care what the other person was doing, so frequently I found myself trying to cook dinner or do the laundry with a kid attached to my ankle. He also didn’t mind who the other person was, as long as they had two legs and the ability to walk. Guests to our home would discover that there was suddenly a child at their feet tying up their ankles.

The rope wasn’t always a rope. Usually, it was a bathrobe cord, which meant that every time I needed to put on a bathrobe, I would stalk around the house cursing while I looked for a cord to tie it with. When I got the brilliant idea of hiding the bathrobe cords, my mother-in-law’s measuring tapes started disappearing, much to her consternation.

Initially, we weren’t sure what all of this ankle-tying business was all about. The whole thing loosely resembled a three-legged race, but we couldn’t think where George would have been exposed to that. We’re pretty sure they don’t do that kind of thing at the therapy centre. Lord, can you imagine trying to do that with a bunch of kids who all have autism? But we went with the three-legged race thing because we just couldn’t think of what else it could be.

At around the same time, both of the boys were discovering YouTube videos featuring Peep And The Big Wide World, a children’s TV show that remains a firm favourite with both of them. You should listen to the theme song – it is very catchy. I have to confess that I find the show itself kind of catchy. Shut up! I know I’m 41 but I can still be a kid, can’t I?

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hqikhlUodC8]

To provide context for the rest of this story, I have to give you a brief outline of the cast of characters in this show.

Peep – a baby chick who has just emerged from his egg, who is very curious and wants to explore the world that he finds himself in.

Chirp – a baby robin who has a strong sense of fairness, and frequently finds diplomatic solutions to a problem. Her biggest ambition is to be able to fly.

Quack – a purple duck who I think actually looks more like a grape with legs. He is obsessed with wearing a hat (a characteristic he shares with George), and he is very vain and bossy. He thinks the sun shines out of his you-know-where.

So anyway, one evening I happened to be passing the kids’ computer while they were watching a YouTube episode of Peep. And all of a sudden the whole rope-around-the-ankle thing fell into place. In this particular episode, Chirp and Quack somehow find their legs joined by a rope, so they have to go everywhere together.

All of this time, George had been replicating this episode.

Can we take just a moment to consider the significance of this? George was engaging in PRETEND PLAY! For a child with autism, this is through-the-roof HUGE! What made it even bigger was the fact that it was pretend play that required a partner.

Hmmm. Pretend play that incorporates social interaction. To borrow a phrase coined by my online autism support group, Holy Moly Shit! This represents an exciting chapter in George’s development. He has outgrown this phase now, and he has not engaged in much pretend play since then, but it’s the potential that strikes me. The fact that he CAN. If it’s happened once, it will happen again.

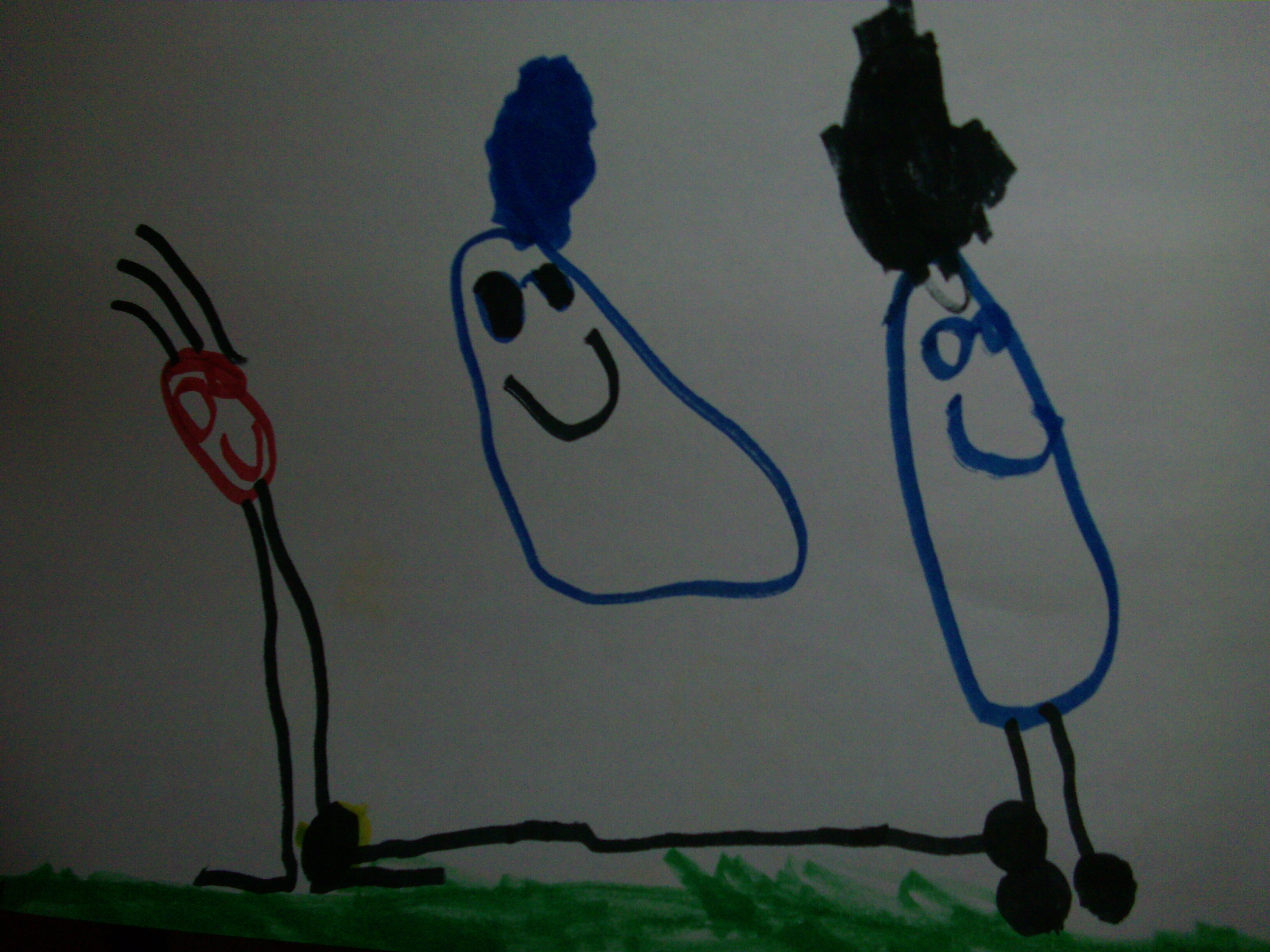

Shortly after the ankle-tying phase came to an end, George drew his first real picture (i.e. the first picture that actually depicted something other than scrawls and scribbles). I was most amused – and highly thrilled – to see that the picture was an illustration of George’s favourite Peep episode.

This kid astounds me. From time to time, he does these amazing things to remind me of what he can achieve if given the opportunity.

Archimedes said it best: “Give me a place to stand and I can move the earth.”